Open science and reproducible literature searches

How to create a reproducible and systematic literature search for your research projects

Image credit: Photo by Janko Ferlič on Unsplash

Image credit: Photo by Janko Ferlič on UnsplashThe literature search is the first step required for conducting a literature review. There are many tools available to search “the literature”, this evergrowing mass of research articles, commentaries, dissertations, reviews among other type of items. There are, however, very limited resources focussing on how to search the literature.

While I have often seen research students worrying they would miss an important paper in their literature review, I often have no idea how they come up with the selection of papers they included in their final review. As a marker, reviewer, or examiner, I gauge the appropriateness of the articles referenced using heuristics such as:

- are the older key papers mentioned?

- is the review up-to-date? (i.e., are most papers referenced published in the past five years?)

These are heuristics because, in all likelihood, I do not know all key papers or all the recent papers published on the topic I review or supervise. The same goes for published literature reviews, whether they represent a short preamble to an empirical study or aim to provide a snapshot state-of-the art overview of a field such as the reviews published in prestigious journals such as The Annual Review of Psychology or Current Directions in Psychological Science. They represent a good point of entry on a topic, and sometimes can also offer food-for-thought when they are written by leading authorities on a topic, but the method for selecting the articles included in those so-called narrative reviews are often opaque, undocumented and highly subjective.

It is important to pause a moment and consider the difference between a literature search and a literature review. I am not advocating for (or against) narrative reviews. This would be an entirely different blog topic, comparing the relative merits, or rather, purposes of different methods for synthesizing the information inside the articles one has selected for reviewing. Instead, my main point, in this post, is about the need for a more open, systematic, and reproducible method for searching the literature and selecting the articles to synthesise.

Scoping the literature

Whatever the initial source of idea for a new research project, sooner or later, you will need to identify what the topic of your research is and find out what other articles have been published on this topic. The issue nowadays is that any search might return thousands of articles so where do you start? How do you know you have identified the most relevant articles? How do you create a reproducible search?

Search engines and bibliographic databases

Researchers use search engines and academic bibliographic databases to find academic peer-reviewed articles. Bibliographic databases generally focus on articles but can also include conference proceedings and books. Unlike library search engines, however, they also include a lot of meta-data such as subject-specific keywords, research areas, and abstracts. Meta-data is extremely important to help you refine your inclusion and exclusion criteria and ultimately arrive at a manageable, reproducible search string (more details on this below!).

There are freely available search engines such as Google Scholar or PubMed which will return a list of articles based on a keyword search. They are also subscription-only databases such as Web of Science, Scopus, or PsycInfo which you can access through a university database list. These databases will offer superior meta-data to refine your search. The table below lists a selection of these meta-data filters. These filters are crucial to help you reduce the number of articles returned by your search.

| Database | Selected meta-data filters |

|---|---|

| Google Scholar | Sort by time, relevance; Custom data ranges |

| PubMed | Sort by time, relevance; Custom data ranges; Article types (e.g., Classical articles, Review, Peer-review…); Text availability (Abstract, free full text…); Species (Humans, Other animals); Subjects (AIDS, Cancer, Systematic reviews…); Languages; Search fields (e.g., MeSH major topic, MeSH subheading or MeSH terms…), Ages (e.g., Child, Infant, Adults, Aged…); Export batch size: 200. |

| Social Sciences Citation Index | Sort by time, relevance, times cited, usage count…; Custom data ranges; Document types (e.g., Articles, Review); Languages; Web of Science Index (e.g., Conference Proceedings Citation Index-Social Sciences and Humanities, Social Sciences Citation Index); Author Keywords (DE); Keywords Plus® (ID); Usage Count Since 2013 (U2); Web of Science Categories (WC); Research Areas (SC); Export batch size: 500. |

| Scopus | Sort by time, relevance, cited references…; Custom data ranges; Document types (e.g., Article, review…); Subject area (Social sciences, Multidisciplinary…); Document type (Article, Review…); Keyword; Source type (Journals, Conference Proceedings…); Language; SciVal Topic Prominence; Indexed keywords; Export batch size: 2000. |

| PsycInfo | Sort by time, cited references; Custom data ranges; Publication type (e.g., Peer-reviewed journal…); Subject headings; Human; English language; PsycARTICLES Journals; Export batch size: 200(?). |

Identifying key search terms

The first step in scoping the literature is to identify the relevant key search terms for your topic. There are several channels you can use to do so. You can ask experts (e.g., your supervisor and/or your librarian). You can also use the databases.

The research topic of the TORR project is scholarly peer-review. In particular, we are looking at better understanding what information peer-reviewers may use when reviewing a grant proposal (as opposed to a journal article) in the humanities and social sciences?. We have already conducted a heuristic search to identify key recent papers but we are now at the stage where we want to produce a synthesis of past research on this topic. We are ready to start scoping.

The aim of the scoping exercise is to create an overarching research question that will inform how we select articles and what information we retrieve when we read them. Scoping also allows to try and test our search strategy.

The scoping exercise involves a few basic steps:

- Select one database (e.g., Google Scholar, Medline, or if you have access via your uni, Web of Science, Scopus or PsychInfo) and search for keywords and key phrases relevant to your topic

- Run an initial search with an initial search string, screen the results to assess the proportion of relevant articles based on title and keywords, note down additional relevant keywords or key phrases to refine your search string.

- Repeat with (an)other database(s).

The key here is to (a) identify the keywords that other people have used to label your topic, and (b) find a balance between the extent to which your search string is able to capture all relevant articles (sensitivity) and the extent to which it is able to exclude irrelevant articles (specificity).

Each of the databases listed above have their own specific strengths and weaknesses but they all offer ways to identify relevant keywords and key search terms.

Scoping step 1

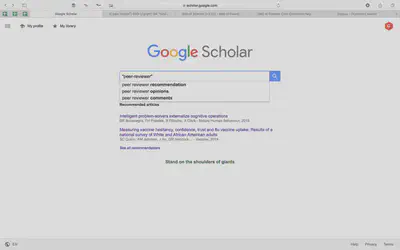

I like to use Google Scholar for my initial keyword search because when you enter a keyword, you get prompts for popular search expressions.

peer reviewers, you should enter it as a search expression using quote marks: "" to increase the specificity of your search. Otherwise you will also pick up articles which mention anyone of these words separately.The screenshot below shows the search expressions coming up when I typed "peer-reviewer" in Google Scholar on the 31st of March 2019.

peer-reviewer in Google ScholarThis gives you several prompts for search expressions which are relevant to our topic such as peer reviewer recommendation or peer reviewer opinion as well as peer reviewer comments.

On the basis of this first scoping, I skim through the articles return and I start building up a list of keywords. Note that the choices I make are subjective and will ultimately define the set of articles which end up in the review.

it does not matter! The key here is to make those subjective choices explicit so that the process by which the final set of articles was selected is reproducible and transparent. You can always amend it (or not), based on comments and suggestions from third parties.Skimming through the search results, I made note of the following further keywords from articles that I would consider to be relevant for our review:

quality,validity,improv?,grad?,assess?,criteria,norm,grant proposals

? at the end of the word indicates that any word starting with the stem would be considered relevant (e.g., improve or improving or improvement). In some search engine, this is replaced by *.I repeated this process in the PubMed database.

After skimming through results from two databases, I came up with the following research question:

What are the *criteria* or *norms* or *standards* or *benchmarks* used by *peer-reviewers* for *assessing* or *reviewing* or *evaluating* the *quality* or *excellence* or *worth* or *value* or *merit* of *grant* *applications* or *funding* *proposals*?

Scoping step 2

Once you have a research question, you need to write up a search string which you use in the database of your choice. All other databases listed above have their pros and cons and again, there is no right or wrong choice. You simply have to decide based on your research objectives. PubMed is orientated towards medical fields, for example, and in our current research we are focusing on social sciences and the humanities so I will probably not include it. PsycInfo may be too specific although we are interested in the cognitive processes involved in peer-reviewing so we plan to test the string in this database. We will also test run it in Medline (EBSCO) because the research proposals in our project are likely to relate to health and well-being topics.

Next, you will need to refine and filter the search results and define inclusion and exclusion criteria.

This translates into the following reproducible search string:

(

criter?ORnorm?ORstandard?ORbenchmark?) AND (peer-review?) AND (assess?ORreview?ORevaluat?) AND (qualityORexcellenceORworthorvalueORmerit) AND (grantORfunding) AND (proposalORapplication)

We may refine the search string depending on the quantity and relevance of the outputs returned by this search.

Once you have selected your database(s), you will need to define your search string. A search string is a combination of keywords and logical operators such as AND, OR, NOT and proximity operators such as NEAR or SAME.

For example, a topic search string for the project above could be:

TS = (peer AND review AND (grant OR funding))

This search returned 2,346 hits on the 8th of January 2019 in the Web of Science Core Collection. That’s a little too many to process! Moreover, examining the title of the second article: Perceptions of the attractive factors for adopting public-private partnerships in the UAE suggests that the search is not diagnostic enough.

At first sight, if a search string returns many articles that are clearly irrelevant to the research question you had in mind, it is a sign you need to refine your search string. Ideally, a search should return a good number of articles that are mostly relevant to your question, at least on the first page. What a good number looks like is difficult to define. In my experience, if you return more than 200 articles, your search string is not precise enough. If you return less than 20 articles, your search is likely to be too narrow.

To narrow down (or expand) your search, you can add (or remove) constraints. In our example, we could limit the search to articles which explicitly mention peer, review, and grant or funding in their title only rather than as a topic that could be picked up anywhere in their title, keywords or abstract.

Let’s try the following search string:

TI = (peer AND review AND (grant OR funding))

This now returns 150 hits. Furthermore, looking at the titles of the first page, all articles seem to be relevant for our topic:

- Peer review of health research funding proposals: A systematic map and systematic review of innovations for effectiveness and efficiency

- The foundation and consequences of gender bias in grant peer review processes

- Assessment of potential bias in research grant peer review in Canada

- Peer Review Practices for Evaluating Biomedical Research Grants A Scientific Statement From the American Heart Association

- Blinding applicants in a first-stage peer-review process of biomedical research grants: An observational study

Now, this does not mean that this search string has found all articles relevant for the topic (the miss rate could still be high). But it gives a good and manageable starting point to begin the review. Moreover, we can make the reasonable assumption that if someone wrote an article about peer reviewing of grant applications and failed to mention either peer or review or grant or funding in their title, they might deserve to be taken out of our initial reviewing sample!

If using the title only search returns too few hits, you may use a less common, but very useful technique, to further refine your search by including a proximity constraint. For example, our search is concerned with the review of grant proposals or research funding applications. So relevant articles should mention these terms in close proximity. To indicate this in your Web of Science search, you can replace AND with the proximity operator NEAR/X where X is the number of words that can separate your key concepts.

TS = (peer NEAR/5 review NEAR/5 grant) OR TS = (peer NEAR/5 review NEAR/5 funding)

This returns 409 hits. This is still a large number of articles to review but if you have a time or the resources, you may find articles you wouldn’t have picked up with the title search. Skim-reading through the titles returned by this particular search reveals still some irrelevant articles early in the sample (e.g., the fourth most relevant article is titled: “JACK trial protocol: a phase III multicentre cluster randomised controlled trial of a school-based relationship and sexuality education intervention focusing on young male perspectives”). Looking at the abstract, this particular article was picked up because it included the following sentence: “Results will be published in peer-reviewed journals and disseminated to stakeholders. Funding is from the National Institute for Health Research.”

For the purpose of this exercise, I am not seeking to establish an exhaustive list of articles on my topic (i.e., I am not too concerned about the miss rate of my search) but rather I am concerned with the quality of my sample (i.e., I care about my initial hit-rate), so I decided to retain the search strategy based on query limited to the title field to begin my review. Bear in mind that you can always identify more relevant articles from the reference sections of a small sample of relevant articles.

In fact, rather than expand my sample, I also limited it further by selecting only the outputs published in the last 20 years, which reduced my sample to 95 hits. Among those, I still found articles and other types of outputs such as letters, editorial materials, and news items. However, since the aim of this review is to identify what assessment criteria are used by peer-reviewers, I decided to keep all types of outputs for my initial review. If my review was intended to review existing empirical findings on a topic, however, I would refine my search further to select articles only as document types.

To sum up, there are many decisions which you must consider before you even start of your literature review for your research project. First, you need to refine your research question using keywords and key concepts. Second, you need to define a search strategy to identify relevant articles in a bibliographic database. The quality of the sample of outputs you will identify will depend on the quality of your search query. If your initial search returns too many irrelevant articles, try limit your search to a few key concepts in the title. If your initial search returns too few articles, try to expand it by adding synonyms (e.g., as in my example using (grant OR funding)) or by conducting a proximity search within the topic field.

Once you are happy with your selection of articles, you can export them. My advice would be to export them as a tab-delimited file with the full record and cited references which you can open in Excel and also as a BibTex file which includes Author, Title, Source, and Abstract information and which you can import into Zotero to manage your references.

To be continued…

This post is work in progress, so comments are welcome! If you know of other strategies or approaches for identifying appropriate keywords for reproducible systematic literature searches, please do leave a comment below or get in touch, I would love to hear!

Further reading

- James, K. L., Randall, N. P., & Haddaway, N. R. (2016). A methodology for systematic mapping in environmental sciences. Environmental Evidence, 5(7). https://doi.org/10.1186/s13750-016-0059-6

- Click here to see an example of a cumulative literature review and here for a how-to guide to conduct one.